1. Select a discrete app icon.

notes

How Abusers Coerce Recantation

From behind bars, abusers often follow a pattern of manipulation to coerce survivors into recanting

- Feb 05, 2025

Key Takeaways:

- Coercion Drives Recantation in Domestic Violence Cases: Many survivors recant their testimony due to manipulation by abusers, who use tactics such as gaslighting, sympathy appeals and shared memories to erode independence and coerce compliance. These strategies often occur even under no-contact orders.

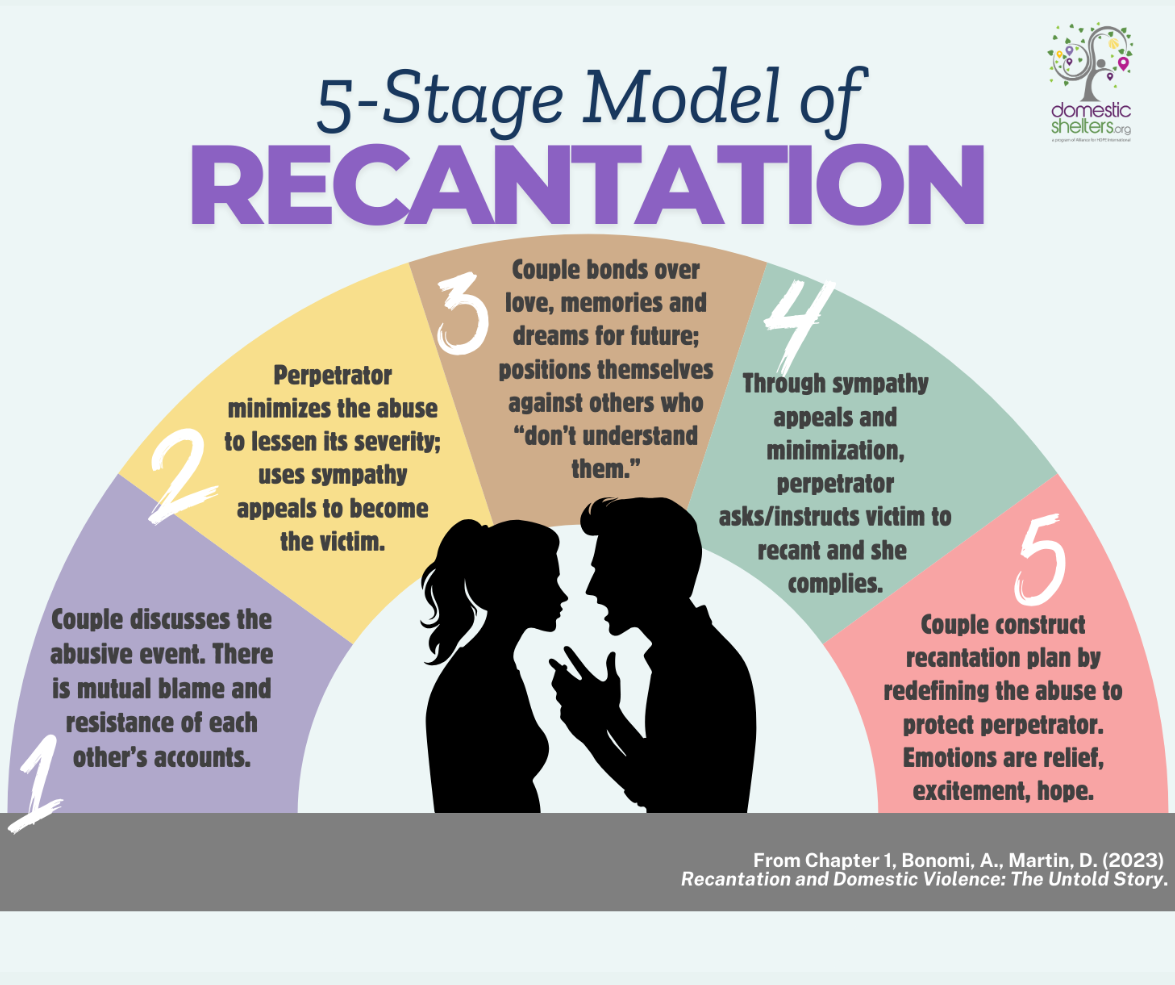

- 5-Stage Model of Recantation: The process includes gaslighting the survivor, minimizing abuse, fostering a false sense of connection, directly pressuring the survivor to recant and reconstructing events to protect the abuser. These methods reinforce coercion and can involve enlisting others to further intimidate or manipulate the victim.

- Empowerment Through Awareness and Support: Survivors can resist manipulation by blocking abuser contact, working with advocates, reporting no-contact violations and seeking trauma-informed therapy. Prosecutors and advocates play a crucial role in ensuring abusers are held accountable despite attempts to undermine justice.

Imagine you see a statistic that shows the rate of domestic violence is dropping. The number of arrests and convictions for abusers has decreased steadily. You’d be inclined to think this is good news, right?

Unfortunately, these numbers are not always what they seem. In a surprisingly high number of cases, abusers themselves are responsible for this decrease. Studies found that in 80 percent of domestic violence cases that reach the court system, survivors have recanted or refused prosecution, often because of the manipulation of their abusive partners from behind bars.

Recantation is when someone takes back their statement or testimony regarding events that led to criminal charges of a perpetrator. In domestic violence cases, survivors may recant for various reasons:

- Fear of future abuse escalating

- Promises of change from abuser

- Financial dependence on abuser

- Distrust of the criminal justice system

- Fear of deportation

- Complex caretaking needs with the abuser

Dr. Amy Bonomi, Dean of College of Health and Human Services at San Diego State University, founder of Social Justice Associates and consultant for U.S. Dept. of Justice, along with David Martin, J.D., Senior Deputy Prosecutor with King County Prosecutor’s Attorney’s Office, released their findings in 2023 after studying jail calls coming from abusers to their partners. In their book Recantation and Domestic Violence: The Untold Story, they explain the pattern they uncovered that ultimately led many survivors to recant.

5 Stages of Recantation

In all of the cases Bonomi and Martin studied, the survivors were women and the perpetrators were men. All of the subjects knew they were being recorded through an automated message. And, most shockingly, in all of the cases where the survivors recanted, they had been previously strangled during their relationship with the abuser, a tactic that’s been shown to be the number one indicator of future murder.

While all of the survivors had no-contact orders in place with their abusive partners, litigators prioritized witness tampering over the violation of the no-contact orders. Accepted by most courts as evidence, these calls would show without a doubt that the abusers were the cause of the survivors recanting.

The 5-stage Model of Recantation that Bonomi and Martin created after listening to hours of jail phone calls outlines what the abuser said, how the abuser was saying it and how the victim responded, all of which followed a similar pattern. Abusers might not go in the exact order of the stages and may come back to a stage more than once, but ultimately, by following this pattern they successfully coerced the survivor to recant.

Stage 1: The researchers say that, in this beginning stage, the abuser and survivor often argued about what happened in the abusive event. There was gaslighting on the part of the abuser, who tried to convince the survivor that her memory of the events was incorrect. Bonomi says, “Early calls showed a lot of resistance, sometimes [the survivor] hanging up on the abuser. There was anger, blame and regret among both abuser and victim.”

In one of the actual phone calls Bonomi and Martin listened to, the abuser tried to equate his physical abuse with the survivor’s verbal reaction.

Survivor: “Why are you constantly beating on me though?”

Abuser:” I’m not constantly beating on you. You don’t understand that you’re beating on me with words, and I can’t defend myself.”

Survivor: “With words, but I don’t hit you.”

Abuser: “Hit you? You hit me so f*cking hard with words … and I’m a very fragile person, mentally.”

Survivor: “I’d rather be verbally attacked.”

Stage 2: This stage is categorized with the minimizing of his abuse. The survivor’s self-empowerment and independence begin to erode. Bonomi says abusers use a sympathy appeal, positioning themselves as victims in the relationship and describing how much they are suffering. In turn, the survivor often responds with empathy, helping to soothe their abusive partner.

In one example, the abuser claimed he had a “breakdown” in jail and was put in the psych ward. The abuser’s partner responded with concern. Except, when Martin looked into it, he found that the abuser was lying.

“Many victims have a high level of empathy,” says Martin. “This is an incredibly wonderful human quality…it just makes people susceptible when they encounter someone like [an abuser].”

Bonomi agrees. “[Abusers] are very sophisticated criminals. They know exactly what to say, how to say it, when to say it and who to say it to to enforce the manipulation.”

Stage 3: In this stage, the abuser and survivor bond over early images of life, their dreams of marriage and perhaps children. They also tend to position themselves against others who don’t understand them. There’s an us-against-the-world mentality forming.

“There’s this misconception that the abuser is constantly pounding [the survivor] with threats and intimidation and angry aggression …. but we’re seeing something very different,” says Bonomi. “We’re seeing soft, smooth, suave [abusers] as an extension of coercive control.”

Stage 4: In this stage, the abuser asks the survivor to recant. Even when the survivor “complies,” it’s because she has been manipulated and coerced by the abuser. Bonomi and Martin noted that the abuser’s pleas for the survivor to recant are usually reinforced by sympathy appeals, i.e. “If you don’t do this, you know you won’t be able to see me for a year.”

In a real phone call from jail, one abuser tells the survivor she may get in trouble, but that it’s better than him being in jail.

Abuser: “I’m going to the Supreme Court but you gotta be there…you gotta tell ‘em that what you wrote in the police report was a lie, that you’re just mad at me cause you thought I was cheating on you with your cousin.”

Survivor: [Laughs] “Okay.”

Abuser: “If you say that, they’ll automatically let me go.”

Survivor: “Okay.”

Abuser: “You know I love you. They might give you five or ten days but that’s better than me doing 60 to 90 days.”

Survivor: “Me?!”

Abuser: “They’ll probably give you five days for filing a false police report, that’s it.”

Survivor: “I don’t want to go to jail for five days.”

Abuser: “Babe, I just spent five days in the hole. You can’t do five days for me?”

Martin adds that most courts don’t charge the survivor in cases of false reports like this, “knowing what we know.”

Stage 5: Once it becomes clear the survivor will recant, Bonomi says the abuser and survivor then work together to reconstruct the abusive event to protect the perpetrator. The survivor is instructed to downplay the abuse, sometimes asking for anger management therapy instead of jail time. They may blame the criminal justice system for why the abuser is behind bars. The survivor is given a very specific script to say. From the perspective of those unaware of this type of ongoing coercion, it can look like the survivor had been lying and can’t be trusted in the future, when it’s anything but that.

“The [recantation] plan is not always at the suspect’s direction. Sometimes it’s co-created. And that is because of the groundwork that has been laid in that campaign of manipulation and of [the] belief that we’re in it together and everybody else is against us,” says Martin.

How the Abuser Triangulates Others to Influence Recantation

Bonomi and Martin say that the survivor’s coerced recantation is often reinforced by other individuals outside of jail—friends or family of the perpetrator. Abusers may enlist their friends to threaten the survivor not to testify. In one call, the abuser told a friend to drop off money to the survivor—just enough to keep her dependent on him, but not enough to feel like she has independence from him. In another call, the abuser was recorded instructing his friends to go rape his partner if she refused to recant.

Abusers will also use children in order to influence recantation. Speaking to them from jail, they may say things like, “Your mom is mean and evil. Ask her why she hates me. Ask her why she keeps putting me in jail.” Regardless of what abuse the child may have endured or witnessed, there is often still a bond there with their father. The tactic is highly effective, say researchers.

How to Avoid Manipulation by an Abuser

Victim advocates have reported that they regularly use the 5-Stage Model of Recantation as a visual aid to show survivors that they’re not alone as abusers attempt to manipulate them into recanting. Being able to predict an abuser’s next move can take away some of the power of their scheme.

Well-trained and informed prosecutors should not be dismissing cases even if the victim is intimidated into not testifying against her abuser, according to Casey Gwinn, President of the Alliance for HOPE International and one of the leading trainers of prosecutors in the country. Even so, survivors are vulnerable to brainwashing by an abuser. Here are some ways to resist it:

Don’t pick up the phone. As difficult as it may be, block the abuser’s number and don’t answer calls from unknown numbers. Almost all domestic violence arrests result in a no-contact order, so the abuser shouldn’t be contacting you anyway unless it pertains to shared children.

Talk to an advocate for support. Survivors who have the support of an advocate are much more likely to follow through with charges than those who don’t. Contact a local domestic violence advocate. An advocate can accompany you to court proceedings and counsel you on what to expect. Most Family Justice Centers and many community-based domestic violence organizations will assist survivors in court and often accompany them to court to testify.

Report his manipulation attempts. Document every time the abuser violates the no-contact order. Report these incidents to police and the prosecutor. If the abuser ever threatens you into not testifying (a practice called witness tampering), report it. Witness tampering is a crime. Make clear that you are not going to lie for your abuser in court.

Get help from a trauma specialist. Seek out a mental health professional who is trained to treat domestic violence trauma and can help you develop coping techniques. This will help you to remain strong during what is often a retraumatizing process.

Reconsider giving them another chance. It’s important to note that many survivors may feel it’s safe to return to an abusive partner after they’re released from jail or complete a batterer intervention program. Many survivors want to have hope that things will change and that a healthy relationship can be established with this person. Advocates stress that it is only accountability and monitoring that change an abuser’s behavior.

Donate and change a life

Your support gives hope and help to victims of domestic violence every day.