1. Select a discrete app icon.

notes

Is Social Media Bad for Kids?

Almost every teen uses social media, but so do a lot of abusers and predators. The risks of letting kids socialize virtually may outweigh the benefits

- Mar 13, 2024

This piece was originally published in 2017. It was updated in 2024.

The internet has given us lots of things—namely, every piece of information in the world available at our fingertips. It’s allowed us to be accessible no matter where we are. No place is out of reach to update our every move on social media, even outer space. And we’ve condensed all of this accessibility into a tiny, pocket-sized computer we carry with us everywhere we go.

Of course, being more connected than ever is also sort of like we’ve all unlocked the front door to our home. We’ve gone from privacy to an illusion of privacy. We’ve invited people in, and not just some people, all people. For younger individuals, like teens and kids, who are still learning that not every person has the best of intentions, this online transparency can put us at a much higher risk of being targeted for harassment, abuse and violence.

Half of All Teens Experience Online Bullying, and Girls More Often

According to the Pew Research Center, nearly half of all teens between 13 and 17 report they’ve experienced cyberbullying, with the most common type being offensive name calling. Findings also showed 22 percent of teens reported false rumors had been started about them online with another 17 percent saying they were sent explicit images they didn’t ask for.

The majority of teens who experience online bullying are girls, at 54 percent compared to 44 percent of boys. Though the studies don’t show who the abuse is coming from—a stranger, a friend or a dating partner—15 percent of teens say they have experienced someone other than a parent constantly asking them where they are, who they’re with or what they’re doing, a tactic of stalking. Another 10 percent say they’ve been physically threatened. Combine this with the fact that the most at-risk group for dating violence are women between the ages of 18 and 24 and there’s a good reason to be wary about an abuser targeting a teen online.

Hannah Met an Abuser Online at 14

Hannah Craig, Director of Content for DomesticShelters.org, grew up in the ‘90s when the internet was in its infancy. She remembers being introduced to the internet when she was only 11, and quickly found her way to something called IRC, or Internet Relay Chat, one of the first online messaging systems available.

“It was the Wild West then. People didn’t have any idea of the dangers,” says Craig. Sure, parents worried about stranger danger—don’t get into any windowless white vans. Watch out for ax-wielding men in ski masks, that sort of thing. But the internet was just a big encyclopedia, right?

Craig was 14 when she started talking online to a 22-year-old man named Steve.

“It didn’t take very long for the conversation to turn sexual,” says Craig. “I had a gut feeling it was bad, but it was also exciting.”

The two began talking every night. She said it was easy to keep it a secret from her parents. When she was 16, she flew out to see him with a mutual friend. Since she tended to have friends who were older, her parents weren’t overly suspicious.

Nothing happened on the trip, she says. They went on a date, but looking back, she sees it differently.

“In hindsight, it is so gross. He was 23,” says Craig, now 37 and a parent herself. “I think he groomed me from the beginning.” Craig says she had low self-esteem as a teenager, and the attention she got from Steve made her feel more confident and mature. She had a crush that likely wasn’t rooted in the healthiest things, especially because he was mean.

“He said I was fat but that I’d grow out of it,” she remembers.

Trauma-bonding can happen when someone being abused or manipulated feels connected to that person despite the abuse. It’s likely what led Craig to leave home and move in with Steve when she was just 17. He said they could be “roommates.”

That situation quickly led to one where Steve was manipulative and abusive, gaslighting Craig to make her feel at fault for anything that went wrong between the two of them. When she said she wanted to go to college, Steve voiced his dissent. He had successfully isolated her from her family and any other outside support.

It was then that his physical abuse began.

“He passed it off as ‘playful roughhousing’ a lot of times,” says Craig. But when he put his hands around her neck and cut off her airway, she knew it wasn’t a joke.

She endured his abuse for nearly a decade before the two separated. Luckily, she didn’t see Steve again. Today, she uses this experience to shape how she parents her teenage stepdaughter with her partner.

“I am constantly aware of who my daughter is talking to. We’re respectful about it, but she knows that she has no internet privacy.”

Abusers Rely on Shame, Secrecy

“For many teens, they think maybe [the abuse] is merited in some way,” says therapist Kimberly Vered Shashoua, LCSW of Vered Counseling. She works with teens and says that it’s often confusing for this age group to recognize online harassment by a dating partner as abuse. Many are told by their dating partners that they deserve derogatory comments or name-calling. The teenager then feels shame for being what the abuser says they might be—a slut, for instance. Or ugly, fat or unlovable.

“They don’t have anything to compare it to. A teenager is learning how to be an adult. And because abuse is shrouded in shame, it’s very difficult [for teens] to go to their parents and tell them.”

Shashousa says the best thing a parent can do is talk to teens early about warning signs and promise not to punish their child if they come forward about a relationship.

“If a teen is having an online relationship with a 25-year-old and they know their parents wouldn’t approve, it can already feel really isolating. They can feel trapped.”

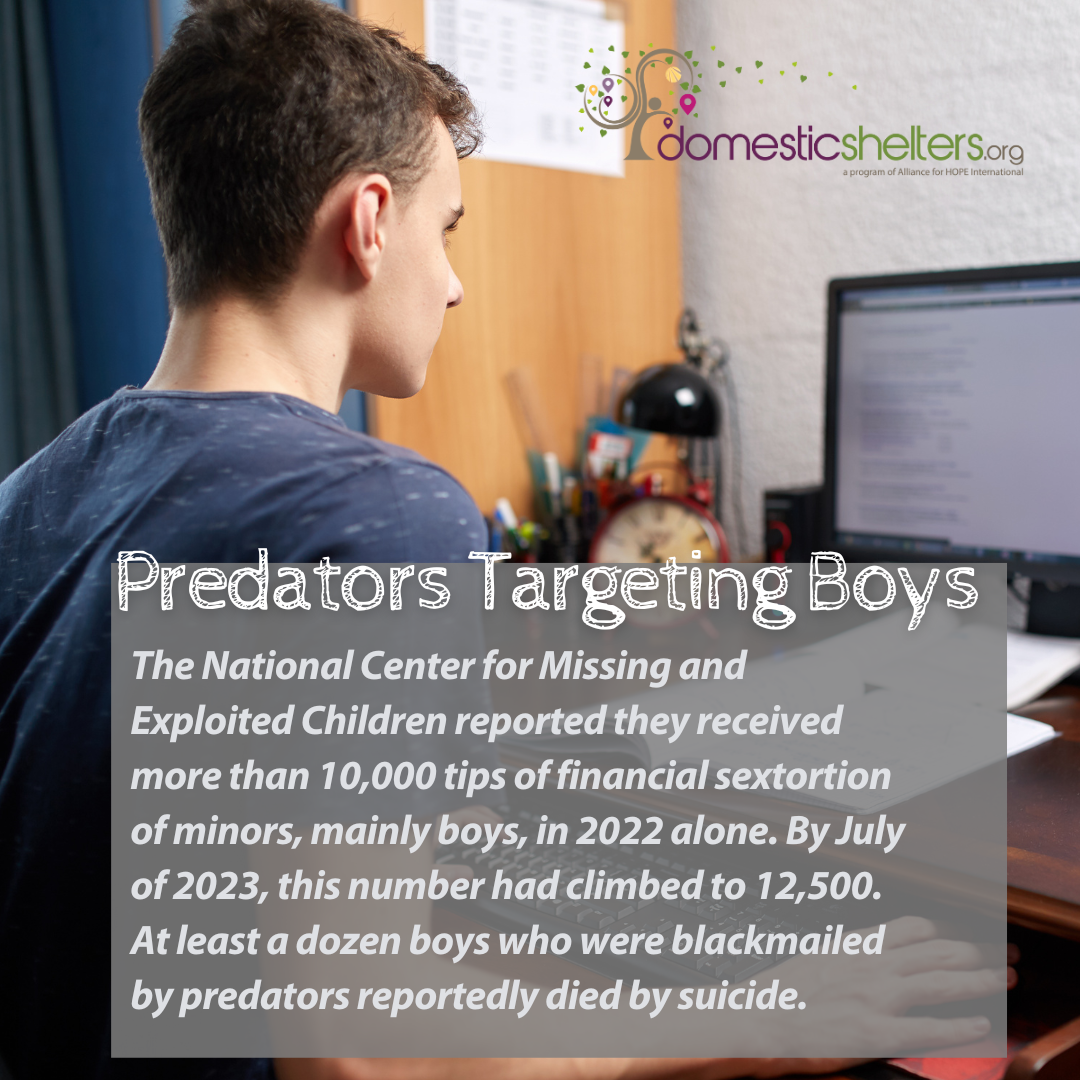

Uptick in Predators Targeting Teen Boys for Sextortion

If abusers targeting teens weren’t enough to worry about, then there’s sextortion, sometimes also called revenge porn. It’s when an individual voluntarily shares explicit or sexual images of themselves and is then threatened with the release of those images unless certain demands are met. According to the Department of Justice, sextortion is the fastest-growing cyber threat to children out there.

Some reports say that teenage boys are the most often targeted for sextortion. In many cases, they may find themselves talking to a stranger online who is posing as another teen. The boy shares an explicit image of himself and the stranger then threatens to release it unless a sizable financial payment is sent, or another condition is met.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children reported they received more than 10,000 tips of financial sextortion of minors, mainly boys, in 2022 alone. By July of 2023, this number had climbed to 12,500. The shame that often goes along with sextortion is devastating. At least a dozen boys who were blackmailed by predators reportedly died by suicide.

SOSA (Safe from Online Sex Abuse), a sex abuse and exploitation awareness nonprofit, advises parents to talk to kids about sextortion even if it seems like something your child would never do. Having an action plan in case they’re tricked by a perpetrator can make them feel more comfortable asking for help.

“To make it less likely that they’ll try to comply with a perpetrator’s demands, talk about the hypothetical scenario in advance so your kid feels more secure at the time. If they already know how law enforcement recommends that people handle sextortion, they won’t have to try to solve the issue on their own,” their site reads.

Also teach children about catfishing, the manipulative practice of gaining someone’s trust through calculated lies in order to take advantage of them. Reinforce that it’s easy to pretend to be someone else online, and that teens should have a healthy skepticism of people they talk to.

4 Ways to Keep Predators Away from Kids on Social Media

The best thing parents can do is to never assume that an abuser or predator can’t find your child. As scary as it sounds, any internet-connected device in the home can let in predators. But with a healthy dose of precaution, you can help build in safeguards to protect your kids.

- Set boundaries. Kids don’t necessarily need unfettered access to the entirety of the internet, even if they might claim it’s sooooo unfair. Consider installing an app that allows you to set limits on what apps they can use and for how long, such as Google Family Link, Bark, Life360 or Norton.

- Have “the talk” more than one time. Even if it garners a few eye rolls, have “the talk” with your child about internet safety. Make sure they understand that just because friends are using social media, it doesn’t automatically mean these apps or sites are safe. Just as you taught them as kindergarteners not to talk to strangers, the same cautions still apply here. Talk to them about never sharing personal information online, such as last name, address, phone number or school, and to never send photos to someone they don’t know. Remind them that anything they post online will stay online forever and may harm their career or college ambitions later in life (not to mention, be embarrassing).

Also cover the healthy relationship talk—a healthy partner won’t expect a teen to be in constant contact with them online and won’t pressure you to send explicit photos. Then, repeat. It’s not enough to have just one talk, so make it a regular check-in to see what they’re up to, what apps they’re using, who they’re talking to, etc. Not every teen will be forthcoming with this information but keeping that line of communication open is important. Build trust with your teen that they can come to you if they ever have questions, feel unsafe or have made a mistake online talking to someone or sharing something they shouldn’t. - Teach kids that not everyone tells the truth online. Predators can easily hide behind any online persona they can make up. A 50-year-old man can pretend to be a 12-year-old boy, then talk to your child through social media or a video game chat feature. Check out these tips for detecting a fake profile online. Teens should also be aware of AI technology that's allowing predators to create fake explicit images using a child or teen's face superimposed into a pornographic photo or video. If a teen sees or is sent one of these images, they should know to report it right away and to not share it with anyone else. Make sure they know that if the image appears to be of them, they will not be in trouble. They are not at fault for a predator targeting them.

- Watch for signs of grooming. Have you noticed your teen isolating themselves more in their rooms than before? Are they constantly sending messages online to someone they don’t want you to know about? Are you seeing new things pop up in their life that you didn’t buy, like clothes or electronics? Is there an adult in their life that’s taken extra interest in them lately and wants to spend one-on-one time with your child? These may be signs of grooming, which is a manipulation tactic of abusers to get someone, usually a young person, to trust them before something more dangerous happens.

Donate and change a life

Your support gives hope and help to victims of domestic violence every day.